By Craig Ebert

A response to the misguided focus on low-quality credits and the elusive supply chain mitigation

The Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) has been in the news a lot recently and not always for the best reasons. Criticisms abound that the VCM is too often bringing low-quality credits to market that result in accusations of “green washing.” There are legitimate concerns about carbon credit quality that must be addressed (and indeed are being addressed as discussed further below), but we shouldn’t let such criticism ruin the progress, success, and potential of the VCM. The VCM is a key tool for investing in climate solutions with two important benefits beyond GHG reductions: fostering climate justice through funding climate projects in the Global South and supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through project co-benefits. The stark reality is that humanity will not avoid dangerous human-induced climate change without carbon credits.[1]

In this article I explain the fundamentals that should drive all of us to this conclusion.

Go Where the Money Is

Perhaps it should go without saying, but the global transition to a low/no carbon economy (sometimes called “net zero”) will require enormous sums of capital to fund the transition. The IPCC has estimated that $125 trillion of climate investment is needed by 2050.[2] Where is this funding to come from? Arguments have been made that the richer nations historically responsible for the climate crisis should fund the global transition. However one feels about this argument, the sad reality is that nations are falling far short of providing the necessary funding. As just one example, as an initial down payment the richer nations committed to funding a Green Climate Fund of $100 billion annually at COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009. Fast forward to 2023 and this initial down payment has not been achieved, with total funding committed amounting to about $89.6 billion.[3] In light of the economic and many other challenges facing the global community, where is the money going to come from?

One obvious answer should be the private sector. Companies around the world can harness enormous sums of capital. Moreover, companies have indicated their willingness to invest in climate mitigation. More than 8,300 companies have voluntarily joined the UN’s Race to Zero campaign, committing to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest.[4]

This is an enormous voluntary commitment of financial resources that can be deployed to support climate justice, but then why are we not seeing the deployment of vast sums of capital to meet these commitments?

Encourage Voluntary Action, Don’t Discourage It

A strong reason for inaction is the “green washing” criticisms companies often face when they do invest in mitigation, particularly carbon credits. Why should any company spend its hard-earned capital voluntarily on climate mitigation if the reaction from its stakeholders is negative? Try going into any boardroom and explaining to the CEO that if the company voluntarily spends X millions of dollars per year on mitigating its carbon footprint, its reward will be public criticism of its actions, protests at its headquarters (or even worse, protests at the homes of senior executives), etc. The quick response will be: “Moving on, what’s next on the agenda?”

Give Credit for Addressing Indirect Emissions

Critics will say that companies should not be investing in carbon credits—they should focus on reducing their direct emissions, often called Scope 1 emissions. This criticism is patently absurd, not because companies should not reduce their direct emissions (they should when they can), but companies are responsible for a lot more than just their Scope 1 emissions.

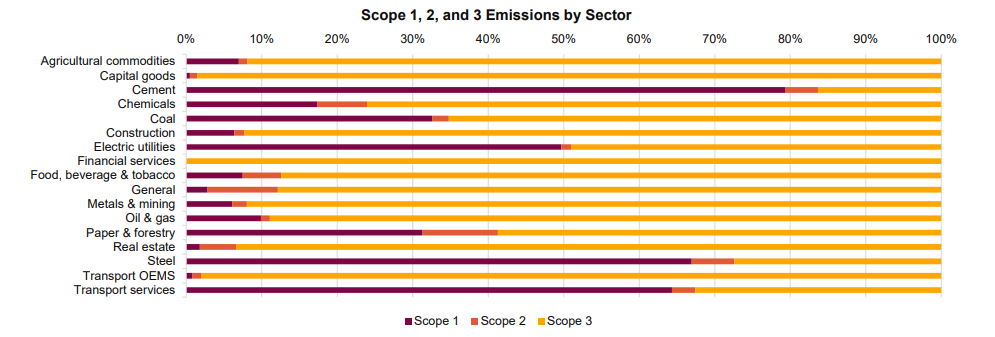

As one example, under the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), companies are asked to identify Scope 1,2, and 3 emissions. For readers not familiar with this terminology, Scope 1 emissions are those emissions that come directly from a company’s actions on its sites (i.e., consuming fossil fuels directly onsite), while Scopes 2 and 3 emissions are indirect emissions that occur beyond the fenceline of a company’s operations (Scope 2 emissions are tied to electricity consumption; Scope 3 emissions refer to everything else affiliated with a company’s operations). The figure below summarizes the relative importance of each of these scopes by economic sector.[5]

Source: CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector

Indirect emissions from a company’s operations vary, but can be quite considerable. For example, indirect emissions from energy-intensive sectors like paper and coal production amount to nearly 70% of their total emissions, with other sectors reporting even higher proportions (financial services reach nearly 100%). For companies to invest in mitigating these indirect emissions, they will need to receive credit for those investments. Otherwise, why should a company invest if they won’t receive “credit” for the investment? Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance to companies about what steps should be taken nor guidance about how companies will get credit for any investments they do make.

Some skeptics have argued that carbon credits (often called “offsets”) cannot be real and should not be counted. That is patently absurd. If one is able to measure emissions using the established GHG accounting methodologies (at both the national and corporate level), one can certainly measure the impact of investing in mitigating those emissions. Nevertheless, that has not prevented attempts to minimize the impact of carbon credits. In fact, The Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative (VCMI) has developed a Claims Code of Practice for companies to follow for any public claims they make about their climate commitments. While there are many facets to the VCMI’s guidance, there are two critical components: 1) Companies are urged to focus on their supply chain emissions, for which there is no specific accounting guidance yet, and 2) Companies can achieve a high level of public recognition for their efforts (Silver, Gold, or Platinum) by also investing in traditional carbon credits. Initial guidance from the VCMI prohibited traditional carbon credits from counting against a company’s emissions (i.e., think of a company getting extra credit for doing more than just reducing its carbon footprint). Fortunately, in late November 2023 VCMI modified its guidance to allow credits to be counted against a company’s Scope 3 emissions. This change is welcome, but still restricts carbon credits to no more than 50% of a company’s Scope 3 emissions, with usage to be completely phased out by 2035. This is a limited step in the right direction, but as noted below, still represents an unnecessary restriction on the use of high-quality credits.

Misdirected Guidance in Supply Chain Focus

This guidance to focus on mitigation investments in a company’s supply chain is perplexing and ultimately undermining credible mitigation efforts and disadvantaging the Global South. My concerns begin with the notion that mitigation actions within the supply chain are somehow functionally different than traditional carbon credits. They are not. The reasoning is quite simple:

- Scope 2 or 3 mitigation options that fall within an individual company’s supply chain, what is popularly referred to as insetting or value chain mitigation, just so happen to be every other company’s carbon credit or offset opportunities.[6] So insetting or supply chain mitigation is just a very specialized subset of traditional carbon credits.

- Presumably, what makes supply mitigation attractive to some is the hope/expectation that companies have more influence over their supply chains and can therefore exercise their leverage to drive to net zero. But companies will vary in the amount of influence they can bring to bear on their supply chains.

- Directing companies to focus on supply chain mitigation is not going to be cost effective. There is a global mitigation cost curve out there (the McKinsey curve just being one),[7] but companies are being told to identify and invest only in that very slim portion of the global mitigation cost curve that applies to their operations. Economics 101 should tell us that severely limiting options will increase costs, likely significantly. For the same amount of voluntary expenditures, companies will accomplish less by focusing on supply chain mitigation rather than the most cost-effective solutions globally to achieve the same target.

There are other problems with a supply chain focus, what I will call “trickle-down environmental economics.” This is a gross oversimplification of a complex world, but most companies are located in the richer countries in the North. How long will it take for mitigation investments to reach the Global South? It is a lot easier for most companies to reach their first order suppliers “down the road” than suppliers 2-3 steps or more removed from their operations (these more remote suppliers are often in developing countries). Of course, each of us can come up with examples where a company can directly influence its global supply chain. But for many companies, they will inevitably start closer to home and eventually branch out to reach developing countries, but how long will it take? Even estimating their Scope 3 emissions has been a herculean effort for many companies. By not encouraging companies to seek carbon credit opportunities in the Global South, we are denying climate justice to those people who need capital investments the most.

A Solution Decades in the Making

Rather than attacking companies for investing in climate projects or creating a new system of crediting for insetting, the answer to proper carbon crediting can be found in today’s voluntary carbon markets. These markets have been developed over the past few decades and offer enormous promise for addressing the climate crisis. Rigorous principles and operational practices have brought high-quality credits to market and will continue to do so, while also making significant contributions to sustainable development in the Global South.

Of course, the traditional VCM is not without controversy. There have been numerous accusations in recent years that low-quality carbon credits have been transacted and do not represent “real” reductions. Indeed, there are projects that do suffer from low quality and have adversely affected public perceptions of the VCM. These shortcomings do need to be corrected so that buyers can rest assured that the investments they are making represent real, high-quality emission reductions.

And being corrected they are. The VCM is a dynamic system that can adapt and respond to market concerns. The Reserve has historically relied on open transparency, multi-stakeholder participation, and public involvement and comment during the establishment and update of our protocols to ensure credit integrity. We support efforts to further raise integrity in the VCM and have applied for assessment against the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) Core Carbon Principles (CCPs). The ICVCM was established for “setting and enforcing definitive global threshold standards, drawing on the best science and expertise available, so high-quality carbon credits channel finance towards genuine and additional greenhouse gas reductions and removals.”[8] The ICVCM’s CCPs provide thresholds for basic principles, disclosure, and sustainable development that high-integrity carbon credits should meet. Through the effort of the ICVCM and others, clear criteria for establishing high quality credits are being defined globally. Given the magnitude of the climate crisis, these efforts must and will succeed.

Why Are We Still Waiting?

At a time when the world is out of time to address the climate crisis, we all know that too little is being done. Yet here we are in late 2023 awaiting the development of “new” guidance for how value chain mitigation is going to be defined and implemented. Really? After decades of working to improve traditional carbon crediting guidance, we all collectively wait for “new” guidance to be introduced? I think all of us know that the introduction of any new guidance will lead to inevitable delays as this guidance is disseminated, digested, and debated. This process could go on for years—years we do not have.

To me the solution is straightforward. Given that we are out of time, any high-integrity action a company voluntarily invests in for mitigating its emissions should count. That includes both supply chain mitigation options and traditional carbon credits—the science demands it. Companies should definitely be encouraged to pursue supply chain actions, but that should be left to each company to decide what is the most optimal, cost-effective portfolio of actions for them. At times I think we forget that this is a voluntary market and companies do not have to do anything (as way too many are doing now while awaiting clarity on the steps they should take). The world needs massive mitigation investments as soon as possible and companies will accomplish a lot more with their voluntary investments if they can decide what meets their priorities (subject of course to the ongoing critical emphasis on high integrity actions).

I have been told that “the train has left the station” on this guidance for companies to focus on supply chain actions. Well, if it has, it is hurtling down the wrong track and someone forgot to build a bridge over the upcoming canyon. Global support for the VCM should focus on endorsing market-based strategies with as few unhelpful restrictions as possible. That is what a voluntary market is all about and the science demands that the world pursue decarbonization as rapidly as possible is pursuit of net zero. Artificial restrictions won’t help in that endeavor.

Craig Ebert is President of the Climate Action Reserve, where he is responsible for ensuring that the organization’s activities meet the highest standards for quality, transparency and environmental integrity. He oversees the organization’s continued leadership and commitment to ensuring offsets are a trusted and powerful economic tool for reducing emissions. In his role, he also leads the organization in identifying and entering into other opportunities that build upon its knowledge and expertise and further its work under its mission and vision.

Any opinions published in this commentary reflect the views of the author and not of Carbon Pulse.

[1] Throughout this article I use the term “carbon credits” rather than “offsets.” While the term “offsets” is often used in the VCM, it is really a misnomer. Offsets are specialized carbon credits often used in compliance carbon markets, where the mitigation activity occurs beyond the boundaries of the compliance program (which typically includes only the largest emitters). In the VCM the “boundary” happens to be the Planet Earth and all mitigation investments take place within this boundary.

[2] https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/the-ipcc-just-published-its-summary-of-5-years-of-reports-heres-what-you-need-to-know/

[3] https://www.oecd.org/climate-change/theme/finance/. There were modest incremental commitments made at COP 28.

[4] https://unfccc.int/climate-action/race-to-zero-campaign

[5] https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/guidance_docs/pdfs/000/003/504/original/CDP-technical-note-scope-3-relevance-by-sector.pdf

[6] For now let’s neglect the inevitable complexities of proper accounting when more than one company shares the same portion of the supply chain.

[7] https://www.mckinsey.com/about-us/new-at-mckinsey-blog/a-revolutionary-tool-for-cutting-emissions-ten-years-on

[8] https://icvcm.org/