By Chris Busch, Director of Research at California-based think-tank Energy Innovation

Recent reports on California’s cap-and-trade program could mislead observers to conclude the system is “collapsing” and undergoing a “meltdown.” But hyperbole isn’t reality, and quite the contrary, the state’s climate policy is succeeding – the most recent data show California is just three percent above its 2020 goal of reducing emissions to 1990 levels as required by AB 32. Meeting California’s 2020 greenhouse gas emissions goal is turning out to be easier and cheaper than expected.

The result drawing so much attention is the California Air Resources Board’s (CARB) most recent allowance auction. Allowances are the tradable emissions permits polluters need to comply with the cap-and-trade program, and auctions are the main way emitters acquire allowances.

In the first thirteen auctions, all allowances offered for use in the current compliance period (“current vintage”[1]) sold out at or above the floor price.[2] However, in the last two auctions, demand was not strong enough for CARB to sell all current vintage allowances at the current price floor of $12.73 per ton. While just five percent of current vintage permits went unsold in February, 90 percent of the current vintage permits went unsold in May.

So if demand for carbon market allowances is weak, how can California’s climate program be on track overall? The answer is simple – the state’s other climate and energy policies are lowering emissions, reducing the need for emitters covered under the cap-and-trade program to acquire allowances. California’s suite of performance standards – such as efficiency standards for buildings and appliances, the renewable electricity standard for utilities, and the low carbon fuel standard for transportation fuels – are principally responsible for falling emissions.

Evolving forward-looking expectations may have also played a role in May’s unexpected auction results – new developments in a lawsuit claiming the state lacks the legal authority to auction permits created market uncertainty. While observers see little merit in this legal action, a California district court issued a set of questions to parties in the suit in April. The smart money is still on the courts upholding the current program’s approach to using revenue through a Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund,[3] but the decision to issue questions have been interpreted by some increasing chances the court will side with the petitioners, potentially disrupting program implementation. Greater legal uncertainty dampens demand for allowances by reducing confidence they will be needed in future years.

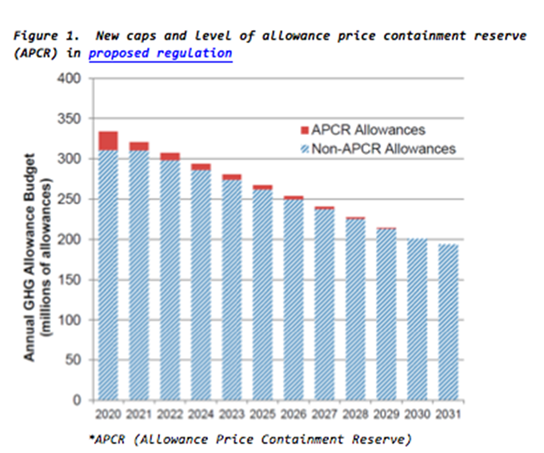

In May’s auction, CARB had not yet defined the shape of the cap-and-trade program after 2020, but it clearly intends to use cap-and-trade to help meet Governor Jerry Brown’s ambitious target of reducing emissions 40 percent below 1990 emissions. In July, CARB released a specific proposal extending the program to 2050. Figure 1 shows new decreasing caps through 2031 included in the proposed regulation.

CARB’s specific cap-and-trade program extension should provide added support for demand at the next auction, though it will probably not fundamentally change auction dynamics in the absence of greater legal certainty. The Brown administration argues its existing authority provides legal basis for extending the cap-and-trade program in this way because AB 32 includes no sunset provision and calls for CARB to “maintain and continue reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases beyond 2020.” Some observers, including the state’s legislative counsel, believe additional legislation will be required for such an extension. However, these legal debates will only be settled when the courts issue a final ruling or new legislation makes the issue moot.

CARB’s specific cap-and-trade program extension should provide added support for demand at the next auction, though it will probably not fundamentally change auction dynamics in the absence of greater legal certainty. The Brown administration argues its existing authority provides legal basis for extending the cap-and-trade program in this way because AB 32 includes no sunset provision and calls for CARB to “maintain and continue reductions in emissions of greenhouse gases beyond 2020.” Some observers, including the state’s legislative counsel, believe additional legislation will be required for such an extension. However, these legal debates will only be settled when the courts issue a final ruling or new legislation makes the issue moot.

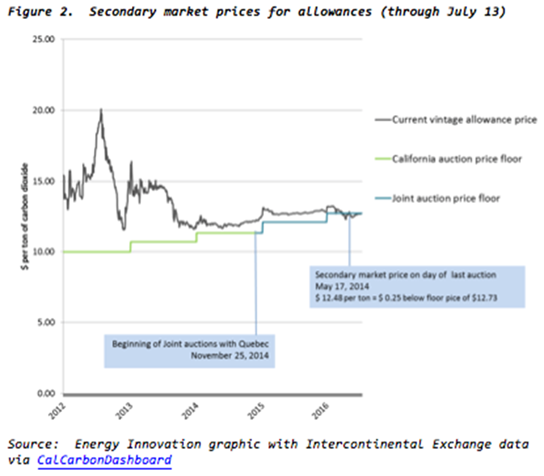

Beyond the CARB-run auctions, the secondary market (referring to all transactions between private parties) for allowances also provides insights into supply and demand. A substantial amount of allowances are traded on the public intercontinental exchange. Figure 2 charts market prices on this exchange in relation to the floor price, and shows how in the months and weeks before May’s auction, the secondary market hinted at the coming earthquake.

On March 29th secondary market prices slipped below the price floor for the first time. One month before the May auction, secondary market prices dipped to their lowest level ever and, on the day of the May 17th auction, secondary market prices were 25 cents below the auction floor price of $12.73/ton.

Since then, prices have recovered, rising over the last 30 days to an average of $12.65/ton in the secondary market. Over the past week, prices have averaged $12.69, just four cents shy of the floor. Nonetheless, the fact that the secondary market remains below the floor price suggests August’s auction will be more like May’s than the first thirteen.

CARB’s new proposed regulation would also provide a stronger mechanism to correct the situation when supply exceeds demand (as indicated by unsold allowances at auction) by diverting unsold allowances from auctions to the allowance price containment reserve (the “reserve”[4]). Currently, unsold allowances are made available again at auction when prices rise above the floor, and this will continue.

However, under the newly proposed design feature if demand fails to increase above the floor price for eight auctions in a row (two years), CARB will begin adding unsold allowances to the reserve. At that time, they would only be available at special reserve auctions, which are only held if prices reach a high price threshold (currently $48/ton and rising over time).

Once formally adopted, this design feature would also put upward pressure on demand at auction as companies face a stronger incentive to buy at relatively low prices today in order to hedge against higher prices in the future.

CARB’s cap-and-trade design has been fundamentally sound from the start, and only continues improving. The new plan to send allowances to the reserve if they are not sold at auction effectively strengthens the program’s automatic stabilizers.

While the unexpected auction results are inconvenient, unsold allowances do not constitute a failure. Though political waves are understandable, California’s cap-and-trade program was never intended to be a revenue-raising measure – its primary purpose is to provide economic incentive to cost-effectively reduce emissions, and here the program is an unquestioned success.

As California has driven emissions down, its economy has taken off: state job growth has outpaced the rest of the nation by 50 percent, showing what decoupled carbon emissions and economic growth look like.

CARB’s cap-and-trade design and the state’s overall approach of a strong suite of performance standards combined with a carbon pricing overlay remains state-of-the-art climate policy. So while breathless reports tell of California cap-and-trade’s imminent demise, we should all pause to inhale and consider how technology, policy innovation, and faster-than-expected economic decarbonization instead anticipate climate success.

Chris Busch Ph.D. is Director of Research at California-based think-tank Energy Innovation, is an expert on carbon market economics who has helped shape California’s carbon market over 10 years of work, and is available for background briefings or on-the-record quotes on state cap-and-trade policy. He has authored papers on California’s general climate policy results as well as specific emissions market reform and transportation sector emissions reform.

In 2008, his research illustrated the initial offset limit proposed for California’s carbon market was too high and could have led to all emissions reductions being accomplished through offsets outside of the energy sector. In 2009 he was appointed by the California Air Resources Board as a member of the state’s Economic and Technology Advancement Advisory Committee.

Chris has led negotiations with environmental groups on cap-and-trade program design, has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals, and has been quoted on California’s climate policy implications in the Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, and Reuters. He has a Ph.D. in Environmental Economics from the University of California at Berkeley (the world’s top-ranked program) and previously served as a climate economist with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

[1] In addition to the current vintage permits, which can be used for the current compliance period running through 2017, the California Air Resources Board’s auctions also offer forward sales of permits that can only be used in the next compliance period. These have sold out intermittently.

[2] The price floor is the minimum price at which CARB auctions will sell permits. The floor price started at $10 in 2012, and rises at a rate of five percent plus the annual inflation rate – equalling 2016’s $12.73 floor price. Technically, the cap-and-trade regulation refers to this as the auction reserve price.

[3] CARB has rigorously required any spending of revenue raised through auctions must be spent in ways reducing greenhouse gases to meet the Sinclair test for what constitutes a fee versus a tax under Proposition 13.

[4] The reserve is the most direct cost containment device in the cap-and-trade program and the first line of defense against prices rising higher, but it’s not the only one. A limited borrowing provision, whereby up to 10 percent of all future caps will be auctioned if the reserve is depleted, acts as a second line of defense.