Almost 75% of the carbon credits issued under the UN’s Joint Implementation (JI) scheme may not represent actual emission reductions, potentially increasing global emissions by some 600 million tonnes compared to if countries had met their CO2-cut targets domestically, according to a study published by the Stockholm Environment Institute on Monday.

The study, one of the first in-depth reviews of the controversial and opaque JI market, casts a long shadow over the cheap Russian and Ukrainian Emissions Reduction Units (ERUs) that the EU allowed its companies to use to offset a big chunk of their obligations under the bloc’s ETS.

The findings put into question some mainly eastern European countries’ efforts to ensure the carbon-cutting projects within their borders were additional compared to business as usual. They also undermine the EU’s reputation as a global leader on tackling climate change and give a stark warning for UN negotiators crafting rules on carbon markets under a new climate deal.

“The implications are particularly serious for the EU ETS. Almost two-thirds of JI credits were used in the EU ETS, so the poor overall quality of JI projects may have undermined the EU’s emission reduction target by some 400 million tonnes of CO2,” said Anja Kollmuss, who co-authored the study along with Lambert Schneider, who currently chairs the executive board of the CDM, the UN’s other carbon trading mechanism.

That figure is around a third of the total reduction in the ETS’ emission cap to be realised during 2013-2020.

After failing to secure JI reforms under the UN, which requires the consensus of all 190+ parties to the Kyoto Protocol or a panel including officials from nations hosting large amounts of offset projects, the EU in 2013 tightened up rules for certain types of ERUs for use in its ETS.

This banned credits from Russia and the Ukraine that didn’t undergo further checks, but was too late to prevent hundreds of millions of units from flowing into the EU and being used for compliance.

Investment in JI projects of any type has since all but ground to a halt, due in part to the EU ban and rock-bottom ERU prices, and as nations wrangle over setting new emission goals under a global climate pact.

SCANT PLAUSIBILITY

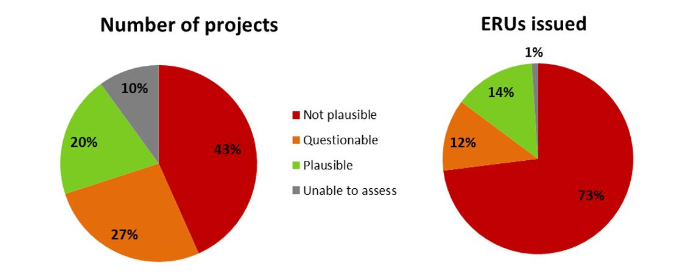

The study examined a sample of 60 JI projects spread across various host countries, types and sizes. It found that 43% of those projects and 73% of the ERUs generated from them were not plausible in terms of their additionality.

Of the six project types examined, it found just one – N2O abatement from nitric acid manufacturing – had overall environmental integrity.

Project types flagged as having low environmental integrity included schemes to prevent fires from piles of waste coal material and capturing gas that would otherwise be flared from oil fields.

The study found that the questionable credits were far more likely to come from JI Track 1, which allows host governments control over auditing projects, rather than Track 2, where credits are subject to checks from a central UN body.

To date, 97% of the 872 million issued ERUs have come via Track 1.

The UN-appointed panel tasked with overseeing JI said the findings reflected its own guidance that the two tracks should be merged.

“This study focuses on that part of JI that is not subject to international oversight, but is instead left up to the individual countries to administer and ensure integrity,” said Konrad Raeschke-Kessler, vice-chair of the JI Supervisory Committee, which oversees Track 2 projects.

“This is a critical distinction, and supports our recommendation made to countries first in 2011 and more recently in the context of a formal review of the rules governing JI: namely that the mechanism in future be run under a single track with international oversight.”

A separate SEI report published in the journal Nature Climate Change on Monday focused on JI’s “perverse effects”, finding three large Russian JI projects that destroyed HFC-23 and SF6 greenhouse gases had in 2011 removed safeguards in their project documentation and increased gas production to unprecedented levels, thus earning more carbon credits.

“If you produced more greenhouse gases only to destroy them and generate more carbon credits, you would essentially be damaging the climate for profit,” said Schneider.

RUSSIA, UKRAINE CONCERN

The studies singled out Ukraine and Russia. By far the biggest issuers of ERUs, they were found to have environmental integrity concerns linked to more than 80% of their offsets.

The next two biggest JI hosts, Poland and Germany, had far fewer issues, with high environmental integrity ratings for 70% and 97% of their credits respectively.

Issuance in both Ukraine and Russia had stalled for several years amid bureaucracy blockages, but spiked in late 2012 as the EU moved to ban the units from its market.

With massive surpluses of governmental AAU emission units, both nations had little incentive to provide strict oversight over the process, knowing they had hundreds of millions of spare units to cancel for every JI unit exported.

“Some early JI projects were of good quality, but in 2011–2012, numerous projects were registered in Ukraine and Russia which had started long before and were clearly not motivated by carbon credits,” said Vladyslav Zhezherin, an independent consultant in Ukraine and co-author of the first SEI study.

“This was like printing money.”

An unnamed UN official quoted by the Guardian said JI had been beset by “significant criminal energy” that had led to a flood of “almost completely bogus credits” in 2012.

The massive issuance of both CDM and JI credits towards the end of the first Kyoto commitment period also contributed to the collapse of credit prices, which fetched over €20 in 2008 but were well below €1 by late 2012.

“This means legitimate carbon projects that really required carbon revenues to be viable may have been harmed by these schemes,” said Schneider.

AUDITING FAILURES

SEI identified failings among third party auditors, known as Accredited Independent Entities (AIEs), hired to check the projects.

“In many cases, they did not perform their auditing functions appropriately. Under Track 1, they had no incentives to do so, as appropriate oversight was not provided, and any non-performance had no consequences,” it said.

“AIEs often failed to identify obvious mistakes, inconsistencies, questionable assumptions or claims, or changes to the project activity or monitoring plan … Moreover, the fact that JI project participants select and pay their AIE may create an inherent conflict of interest.”

SEI identified Bureau Veritas, one of the world’s biggest verification companies employing 66,000 worldwide, as auditing by far the most JI projects, with its popularity among developers increasing at the expense of other auditors as issuance ramped up through 2012.

The study found 77% of projects determined by Bureau Veritas made additionality claims that were not plausible, compared to only 12% of projects determined by other AIEs.

Carbon Pulse contacted Bureau Veritas on Monday. A spokeswoman for the company said she was not aware of the studies, which were published in full at 1600 GMT, and would aim to respond “as soon as possible.”

WARNING FOR NEW GLOBAL DEAL

Both SEI studies echo some of the criticisms that have been levelled at the CDM, the bigger UN mechanism that has so far generated over 1.6 billion carbon credits from projects in the developing world.

The first study made several recommendations for carbon markets under a global climate pact, where most negotiators favour allowing nations to meet their emission commitments including mitigation actions made in other nations but are unclear on the level of oversight required.

“Our evaluation clearly shows that oversight of an international market mechanism by the host country alone is insufficient to ensure environmental integrity,” it said.

While the EU has not allowed for any additional demand for foreign carbon credits in its ETS under its proposal to extend the scheme from 2020 out to 2030, it has left the door open to their use should the bloc take on a deeper overall 2030 emission target than the -40% minimum emission cut it has pledged.

By Ben Garside – ben@carbon-pulse.com