By Alessandro Vitelli

Now that EU ETS compliance is over with for another year, the market can metaphorically wash its hands and move on to the next course of this never-ending feast of carbon: the start of the UK ETS.

The UK government will publish its allocation table of free UK Allowances to industrial installations by Friday (May 14). We already know that the UK will allocate around 58 mln free UKAs to installations and sell around 83 million UKAs at auction this year, and we know that the 2021 cap – according to the legislation – is 155,671,581 tonnes, so by Friday we’ll be able to fill in a few blanks, such as the likely size of any new entrant reserve, cost containment mechanism, etc.

The following week (May 19) the first UKA auction takes place and derivatives trading begins on ICE Futures Europe. And on May 22, the ICE day-ahead futures market opens for business.

(Like in the EUA market, ICE has decided that the UKA contract size will be 500 UKAs in the auctions but 1,000 UKAs for futures.)

So far, so good. But where will UKAs price?

Well, we know the auction floor price is £22/tonne, but we also know that the market is far beyond that level today. We also know that the UK’s Carbon Price Support – the additional charge for fuel combustion – of £18/tonne (over and above the cost of allowances) will remain in place. So UK power generation has at least £40/tonne of costs before we even think about the “real” market price.

It seems self-evident that the only real “peg” we have to hang the cost of UKAs on is… EUAs. For a start, UK utilities are generally assumed to have been hedging any forward power sales this year with EUAs, since there have been no UKAs available.

Because UK utilities won’t be able to use those EUAs for UK ETS compliance, they’ll need to swap them out. UKAs shouldn’t therefore price higher than EUAs, or utilities don’t have the incentive to buy them (yet).

And if UKAs are pricing below EUAs then UK utilities would sell EUAs to buy UKAs, and theoretically prices should converge.

But here’s where it all gets a little tricky, at least as far as I see it.

(Note that all of what follows presupposes that utilities are the driving force in the UK market, and that industrials will have little incentive to sell or buy in the short term. Of course, there are also speculative traders who may want to get involved and that’s where things could get interesting.)

UK auctions will offer 6 million UKAs every two weeks. The total that will be sold in 2021 represents – more or less – the targeted emissions from the utility sector for one year.

Crucially, there is no front-loading of UK auctions to allow British utilities to replace EUA hedges already in place covering forward generation that they sold over the last 2-3 years.

UK fuels combustion emitted 67 million tonnes of CO2 in 2020, according to the European Environment Agency. So, assuming 2.5 years’ worth of forward hedging, that’s pent-up “replacement” demand for 168 million UKAs before the UK ETS even starts.

To be clear: while UK utilities are accumulating UKAs to replace those 2.5 years of EUA hedging, they are also going to be looking to buy additional UKAs for every new forward sale of power they make.

So how easily and quickly are they going to replace all those EUAs that they bought in 2019, 2020, and this year? Again, just look at the maths: If the UK is auctioning 83 million UKAs a year, that’s two years’ worth of sales that utilities will need to buy. And you can add a third year to cover 2021 demand.

Obviously, you only surrender allowances covering a year’s worth of emissions at a time, so in theory there is no problem. But risk management being what it is, there will be pressure on companies to make sure that their positions are properly covered with the relevant permits as soon as possible.

If anyone other than power generators gets involved in the UKA auction market there is some risk that UK utilities may not be able to buy enough UKAs in 2021 to cover their 2021 emissions.

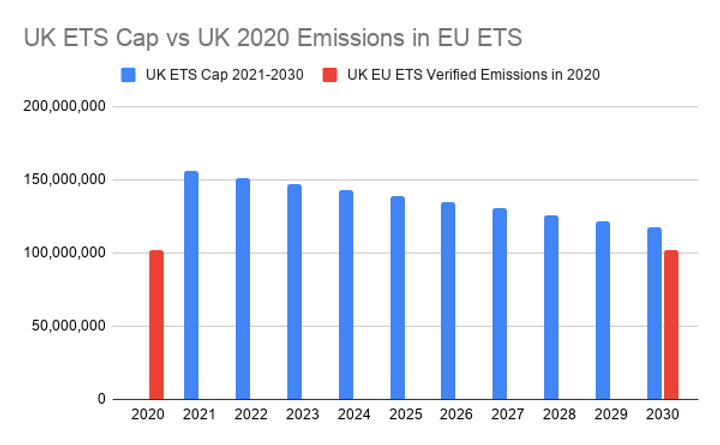

Is anyone going to underwrite the risk of utilities not being able to comply? Because unless this market is considerably more oversupplied than the chart below suggests, UKA prices could really spike.

Does this mean that prices for UKAs could increase far above their EU counterpart? Absolutely, and we might see a test of the Cost Containment Mechanism in the UK before the EU – a nice touch of irony.

It may not be as bad as I may have suggested. After all, many observers (myself included) have said that the UK ETS is going to be oversupplied in its early years. But will it be oversupplied enough to meet utilities’ needs? Take a look:

Source: EEA, UK Govt. Total supply may include New Entrant Reserve, CCM etc

The EU ETS has been working with a structural oversupply of more than 1 billion tonnes since… since forever. It may be true that the EU *now* hands out fewer EUAs than there are verified emissions, but the market will remain “long” until the MSR eats up the 833,000,001st surplus EUA.

The UK ETS has no structural oversupply. Its TNAC starts from zero, and indeed, we don’t yet know how many UKAs will be in the Cost Containment Mechanism in case prices do spike. And there’s two and a half years’ worth of utility demand to satisfy in a short period.

The EU ETS is not really pricing on current demand-supply fundamentals, but instead on expected future demand-supply fundamentals that may or may not arise after a two-plus-year long political process to decide a set of parameters that we don’t yet know much about.

So why should the UK ETS price any differently?

Finally, a word about linking

A coalition of more than 40 industry associations pointed out recently that if the UK and EU markets don’t link by this year, it will be much more difficult to link them once they start to diverge in their key parameters.

The EU is reforming its ETS to meet a new 2030 target of a 55% cut in emissions from 1990 levels. This reform is going to change everything: the cap, the linear reduction factor, the Market Stability Reserve (MSR), industry benchmarks, etc.

And since the UK legislated its ETS into existence earlier this year, it too has upped its 2030 target to a 68% cut from 1990 (and on to 78% by 2035). The UK legislation has already set up one review of the ETS in 2023, in which the government will likely tweak the market to meet the new 2030 target, and another in 2028 to prepare for the second 10-year phase.

Once these two separate reform processes are properly underway – targeting significantly different reduction targets – the chances of regulatory divergence between the two ETSs increase dramatically from where we are today, and so the likelihood of linkage recedes.

From where we stand today it feels like it would require some sort of divine intervention to get the UK and EU to the point of linking before this year is over. So maybe we just need to suck it up and get used to the arbitrage opportunities.

This post was originally published on www.carbonreporter.com