By Olivia Kember, head of policy, The Climate Institute

Australia’s Emissions Reduction Fund is good as far as it goes – but it doesn’t go very far. Described by the government as the centrepiece of emission reduction policy, the $2.55 billion fund pays companies to reduce their emissions. With the completion of its fourth reverse auction the fund has allocated 83% ($2.1billion) of its budget to contract 178 million tonnes of abatement for delivery over the next ten years.

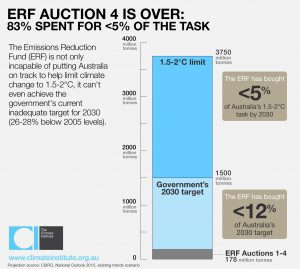

However, Australia emits over 500 million tonnes of greenhouse gases every year, and rising. Based on existing trends, Australia is projected to emit over 3.7 billion tonnes by 2030. At that point, the ERF will have delivered slightly less than 5 per cent of the emission reductions required for Australia to be on a pathway consistent with the Paris Agreement objective of limiting global warming to 1.5-2°C.

Even when assessed against the government’s current emissions target for 2030, an inadequate reduction of 26-28% below 2005 levels, the ERF only achieves 12% of the task.

The ERF has several fundamental flaws as a central policy: first, it doesn’t address the main driver of emissions in Australia, which is the energy sector. Electricity production alone contributes a third of national emissions, due to the dominance of ageing coal-fired generators in the power supply. But the vast bulk of ERF funding has gone to the land sector.

Secondly, it isn’t scalable. Many more billions of taxpayer dollars would be needed for the ERF to make a meaningful impact on national emissions. Even if all abatement cost the average ERF auction price (and much would cost a lot more), the public would need to pay out another $42 billion to put national emissions on the path to 1.5-2°C.

Finally, it simply doesn’t prevent emissions growth. The purchases in the land sector will be effectively wiped out by relaxed land clearing regulations in Queensland and New South Wales. The “safeguard mechanism”, individuated baselines above which top emitters are not supposed to go (with a sectoral baseline for electricity), is set at the level of highest emissions in the last five years, and the rules are full of loopholes.

On existing trends, Australia’s 2030 emissions will be about 8% above 2005 levels.

Meanwhile, the global uptake of clean energy has helped stall global emissions from fossil fuels, which are now falling in major economies like China and the United States. Australia is not just behind its OECD peers, it’s heading in the wrong direction.

The government has pledged to review its entire climate policy framework next year, and develop a long-term emissions pathway. Significant policy adjustments are urgently needed to put national emissions on track – and the longer these are put off, the harder the inevitable reckoning will be.