By Rachel Solomon Williams, managing director, Sandbag Climate Campaign

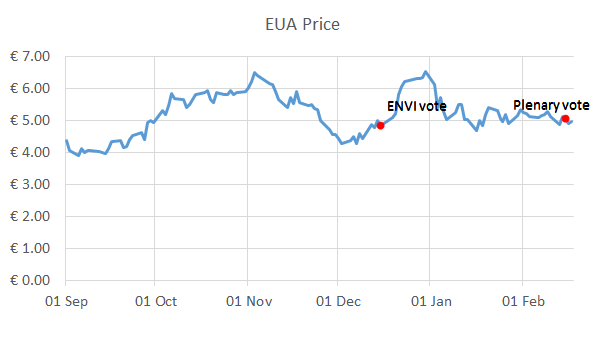

Have a look at the graph below: the price of carbon in the EU over the past few months. Not much happening here, you might think: stuck fluctuating around €5, too low to influence business decisions or drive decarbonisation. It implies an absence of a policy framework driving a carbon price that would be meaningful to the market. (By way of context: one view on what a meaningful price might be was provided by a high-level panel at Davos in January, which found that a global carbon price of $50-100/tonne would be needed to incentivise cleaner investment.)

Source:www.quandl.com; raw data from ICE

There are two red dots on the graph. One of these is the date of a vote in the European Parliament’s Environment Committee (in Dec. 2016), when it endorsed a package of changes to the EU Emissions Trading System for consideration by the Council. The Committee’s rapporteur described the package as “a welcome Christmas gift to all who care about climate change”. I care about climate change. A great Christmas present would have been a signal that the EU’s flagship climate policy might finally change something in the real world.

At Sandbag, the climate thinktank I lead, we watched the market metaphorically shrug its shoulders, and we went off to have Christmas dinner. We then poured all our efforts into arguing that, while the December package made a few improvements, it would in the end do little or nothing to help the EU meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement: the ETS will still contain a large oversupply of emissions, both annually and cumulatively.

The second red dot marks the date when the European Parliament voted on the Environment Committee’s recommendations (Feb 15 2017). The Parliament approved only some of the package as recommended by the Committee, and none of the other amendments which aimed to strengthen it further. The aim had been to bring the ETS into alignment with the Paris Agreement by ensuring that it drives emissions down. That would mean a change to the status quo, to which you might expect a significant market reaction: look, our rulers mean business. But what does the graph show? Another – almost imperceptible – shrug of the shoulders. The carbon price remains stubbornly low, uninterested in the likely changes in policy.

Underlining this situation is the fact that a range of carbon price forward markets, which represent the market’s best view, are showing flat to 2020. We agree with the market that the proposals will do little to raise the carbon price – the proposed reforms are simply not enough to rectify market imbalances. Clearly there simply isn’t sufficient political appetite to push the ETS further.

Here are the crucial elements of the package of changes. First, the cap, which sets the ambition for the ETS, is now scheduled to fall at 2.2% per year from 2021 (proposals to increase this to 2.4% were voted down). Secondly, the highlight of the package was to improve the Market Stability Reserve (MSR) that will operate from 2019 so that it takes slightly more allowances out of the market. However, the MSR will contain over 2 billion allowances in 2020 alone, and also cannot return more than 100 Mt each year. So it doesn’t really make an impact until the late 2050s. Thirdly, and most importantly, proposals to reset the emissions baseline for the cap (“rebase”) in line with emissions were not voted in. The cumulative structural surplus is still increasing every year.

There is one more chance to fix this structural problem in the current round of negotiations: a discussion in the European Council on Feb 28 to set the Council’s position ahead of trilogues. At Sandbag, we continue to advocate for adjusting the emissions baseline to a more realistic level, as the only way to remove enough allowances to make the system work. We urge any member state which is serious about climate ambition to support that adjustment before it’s too late. The other opportunity for those ambitious countries – a crucial change also passed on the 15th – would be to use a new option simply to buy and cancel allowances unilaterally (up to a certain limit). This could at least be done without requiring additional cross-EU agreement. Sweden’s government has already come out and said that it intends to do just that.

The UK government is just beginning to mull over the many choices that will face it as part of Brexit. One of these will be whether or not to stay part of the ETS when the UK leaves the Union. This is a question mired in complexity and not one I can answer here. But the current carbon market shoulder-shrugging (assuming this continues after Feb 28) should give ministers pause for thought if they are serious about UK climate leadership.