By: Danick Trouwloon, Charlotte Streck, Thiago Chagas

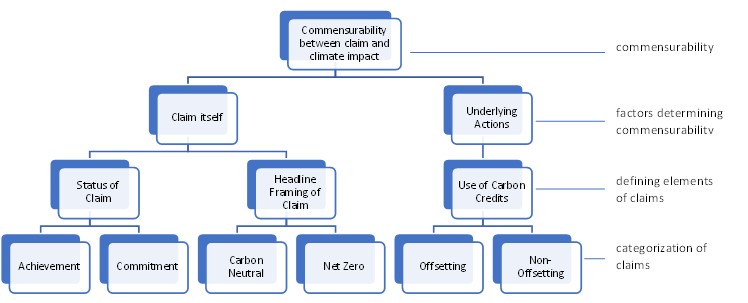

Private sector investments are pivotal for achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goal by mid-century. In this context, voluntary carbon markets have considerable potential to bring about emission reductions and redirect climate finance to the Global South. While public, private, and hybrid efforts are emerging that seek to better govern climate-related claims, currently the engagement of companies in voluntary carbon markets is greatly hampered by the lack of understanding and clarity around the types of claims that can be accurately and credibly made when integrating carbon credits into corporate climate strategies. There is thus a clear need to better understand the current landscape of corporate climate claims and its associated risks, to serve as a basis from which claims can be transparently governed. Our recently published paper in Global Challenges seeks to do precisely that: by reviewing and defining the core elements of such claims, we have sought to contribute a better understanding of how carbon credits are used by companies to make corporate climate claims.

A surge of corporate climate commitments

At the beginning of the year, over 8,000 companies had signed up to the UN-backed Race to Zero campaign, while the Science-Based Targets initiative listed more than 2,000 companies with approved science-based targets. These corporate climate commitments are usually followed by a public announcement that the company intends to become ‘net-zero’ around mid-century, and many companies currently marketing ‘carbon-neutral’ products and services claim to have already fully ‘neutralized’ the greenhouse gas impacts of such products.

As the activities, inputs, and processes upon which climate claims are based are often internal to a company’s operations (and therefore largely unobservable to outsiders), successfully addressing the risks associated with greenwashing demands robust and independent oversight over corporate climate claims. The absence of a strong governance of corporate climate claims leaves room to virtue-signaling and casts a shadow over legitimate and real climate action by companies. This poses reputational, litigation, and regulatory risks to companies. More worryingly, misleading corporate claims can compromise the achievement of the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement by negatively affecting capital deployment and deterring genuine climate action.

In addition, most of today’s corporate climate claims – not only carbon neutral and net zero, but also carbon negative, carbon free, and climate positive – rely to a greater or lesser extent on the use of carbon credits generated from carbon markets. But few companies release details on whether offsetting is used to complement or substitute investments into abatement of greenhouse gas emissions generated by a company’s operations or within its value chain. A recent study targeting German consumers found that only 3% of the surveyed consumers were aware of the details behind the popular ‘climate neutral’ claim.

While the risks associated with corporate claims should be addressed through more robust governance, they should not discourage investments in carbon markets. To fully maximise the potential of carbon markets, it is important that claims involving the use of carbon credits accurately reflect the nature of that engagement. This requires full and complete transparency over the actions backing corporate climate claims, a common set of definitions and criteria for such claims, as well as assurance and oversight over claims made by companies. In particular, greater clarity is needed around three core dimensions of carbon credit-related claims: (1) the intended use of carbon credits; (2) the framing and meaning of headline terms; and (3) the claims’ temporal aspect.

Corporate climate claims and their defining elements

Intended use of carbon credits

While offsetting will likely still be needed around mid-century to neutralise emissions, carbon markets can serve a much wider set of functions. For instance, leading organisations are exploring the use of carbon credits for non-offsetting purposes, where companies contribute to a global net goal rather than compensating for emissions occurring within their own value chains. Generally referred to as “mitigation contributions”, carbon credits that are acquired for purposes other than compensation or offsetting avoid diversion from the much-needed mitigation action within corporate operations and value chains. A remaining challenge is to define a claim related to such mitigation contributions that is more compelling for companies and consumers.

Clarity in headline claims: Climate neutrality and net zero

While corporate climate claims contain a gamut of terminologies (such as net-zero, carbon neutral, carbon zero, climate positive or carbon negative), net zero and carbon neutral are the terms that companies have used most often to date. The use of carbon or climate neutrality dates back to the early 2000s and serves as official seal of a number of standards, such as CO2-Neutral by Carbon Trust, the Carbon Neutral Protocol by the Climate Impact Partners, and the Climate Neutral Certified Standard. In turn, net zero gained particular momentum with Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2018 Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5C, and the need to achieve net zero carbon dioxide emissions globally by 2050, followed by the Science-Based Targets initiative’s updated set of target validation criteria for corporates willing to align their strategies with the latest science.

Each of these claims poses its own challenges. In the case of net-zero claims, companies must clearly communicate whether their net-zero claim is merely aspirational in nature and whether they are in fact progressing on a science-aligned pathway to net-zero (but are not net-zero yet), in addition to reporting annually on their trajectory and progress. In the case of carbon neutrality claims, companies should inform stakeholders of: (i) how they define carbon neutrality and the scopes of emissions covered; (ii) how they seek to achieve it and the extent to which they rely on offsetting; and (iii) how this carbon neutrality claim actually fits into the company’s Paris-aligned decarbonization pathway.

Future commitment or confirmation of achievement

Net zero and carbon neutrality claims also differ in the time and trajectory of effort. Net zero claims are often commitment claims that are aspirational in nature and represent voluntarily set goals that a company wishes to achieve at some point in the future. Such commitments pose the risk that they will not be met despite a company’s genuine efforts, or that they are a disguise for a company taking little to no action. Carbon neutrality claims are often achievement claims that convey a concrete statement of fact, as opposed to a promise or aspiration to reach a goal by a future date. Achievement claims risk that to give consumers the false impression that the consumption of a carbon neutral product or service ceases to be harmful. Due to the volume of global climate mitigation required to keep temperatures to 1.5 or 2C above pre-industrial levels, achievement and commitment climate claims must come in tandem and be formulated in a manner that reinforces each other.

Our review underscores the importance of transparency around the use of carbon credits, which functions as an overarching principle for all three defining elements identified in our paper. The proposed categorization of corporate climate claims has proved particularly useful in elucidating the differences between what it currently means to claim a positive climate impact that a company has already accomplished, versus signalling a future climate ambition. But this review only confirms the need to develop a governance for corporate climate claims. Private initiatives, such as Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity initiative with its Provisional Claims Code of Practice and the Gold Standard Claims Guidelines, mark important steps into that direction and define a pathway that will find its conclusion in the public regulation of corporate claims.

Any opinions published in this commentary reflect the views of the author and not of Carbon Pulse.